167

Chapter 10: Environment and Transport

375 kilo-tonnes of oil equivalent (ktoe) to 1045 ktoe (1 toe

is the amount of energy released by burning 1 tonne of

crude oil). This was followed by a decline of 44% up to

2012, while 2013 saw an increase of 3.4% to 607 ktoe,

and this upward trend is continuing.

Marine and Navigation

Tonnages handled by Irish ports, while increasing in

2014, were still 12% below 2007 levels. The number of

vessels handled was 24% lower in 2014, suggesting a

move towards fewer larger vessels. This transport sector

involving Ireland’s cargo ships and tankers is simply known

as “navigation”. Navigation energy demand is estimated

based on sales of marine diesel. For the period 1990 to

2013, the estimated energy demand increased from a low

base in the early 1990s of approximately 7 ktoe to a peak

of 81 ktoe in 2008, declining to 57 ktoe in 2013. The

trend for energy demand in this mode is currently poorly

understood.

What’s Being Done

Energy Efficiency

Initiatives to increase energy efficiency in the

transport sector are in progress.

Ireland’s third National Energy Efficiency Action

Plan (NEEAP) was launched by the Department of

Communications, Energy and Natural Resources (DCENR)

in 2014. The NEEAP sets out a suite of policies and

measures to deliver savings resulting from energy efficiency.

The transport sector accounts for 14% of the total

energy efficiency savings identified. The majority of the

energy savings (66%) are expected to come from the EU

regulations on improved fuel economy of new private cars,

but this assumes that the energy efficiency figures supplied

by the various vehicle manufacturers can be validated.

According to research by the International Council on

Clean Transportation (ICCT), real-world emissions of CO

2

are up to 40% higher than emissions measured in the

testing lab, with the largest discrepancy observed in hybrid

cars (EEA, 2016).

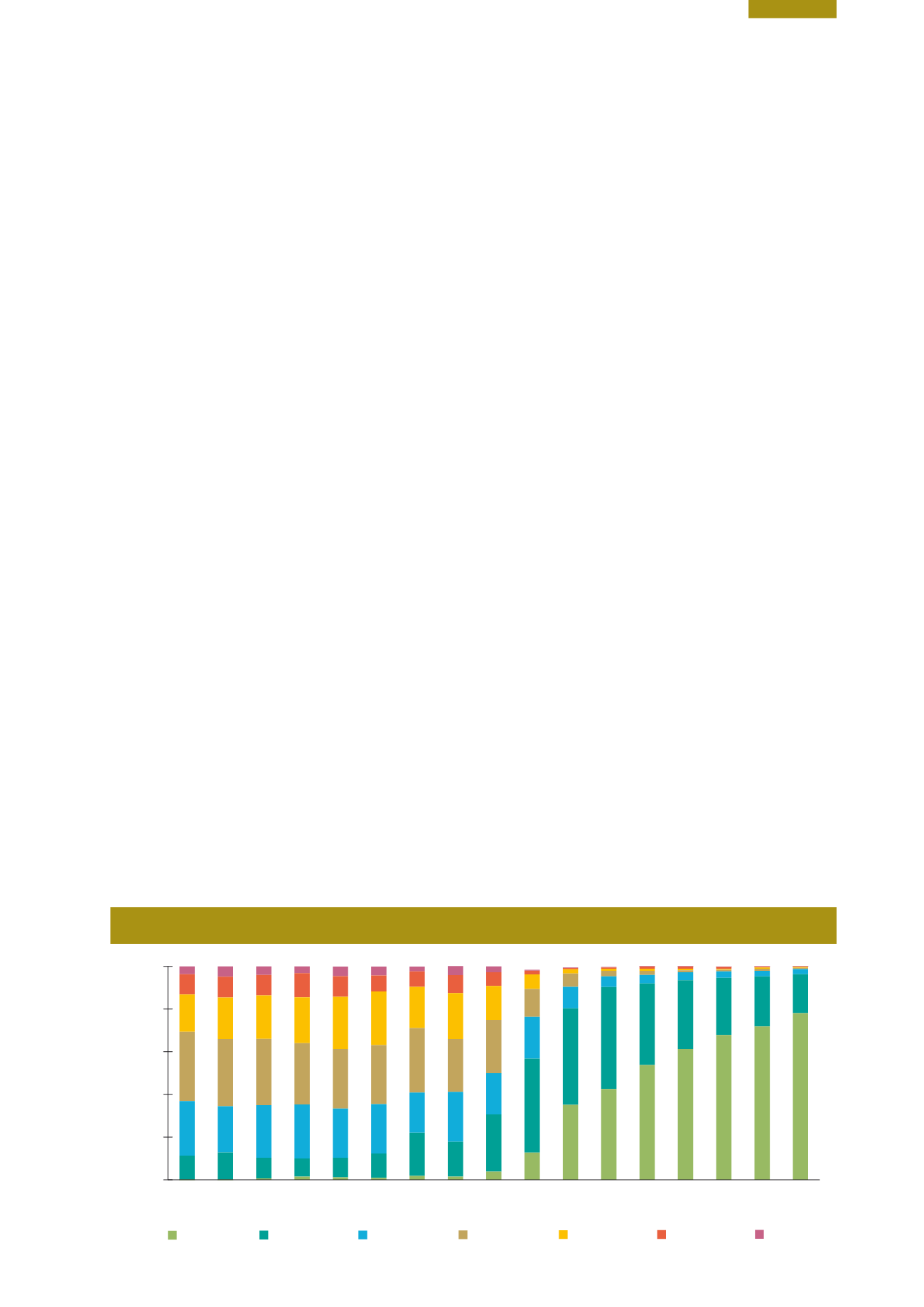

The charging system for Vehicle Registration Tax (VRT)

and motor tax for private vehicles continues to promote

the purchase of energy-efficient vehicles. In 2013, 61%

of new purchases were in Band A (1–120 g/km) and 32%

were in Band B (121–140 g/km), while cars with CO

2

emissions of 140 g/km or higher accounted for just 7% of

new car purchases (Figure 10.6). Whilst a successful policy

from the perspective of CO

2

, this tax transfer did lead to

higher environmental NO

x

and particulate emissions as

consumers migrated to low-CO

2

diesel cars. A significant

portion of the Irish passenger car (PC) fleet still uses older

exhaust emission reduction technologies, such as Euro II

(1997-2001) and III (2002-2005) , but this is changing as

newer technologies such as Euro IV and V become more

dominant (EPA-UNFCCC, 2016). The potential impacts,

particularly the effects of NO

x

emissions resulting from

continued dieselisation (increase in relative numbers of

diesel vehicles) on ambient pollutant levels and therefore

human health, are becoming more clearly understood and

must also be factored into policy development in this area.

The environmental efficiency of such a taxation measure is

therefore questionable.

Initiatives are under way to modernise the public transport

fleet by introducing reduced emission vehicles. There is a

commitment to establish a Green Bus Fund to cover the

differential between the cost of a conventional diesel bus

and the cost of an alternative fuelled equivalent. This,

and other transport measures, are included in the White

Paper on Energy Policy

Ireland’s Transition to a Low Carbon

Energy Future 2015‑2030,

which was published in 2015

(DCENR, 2015).

Figure 10.6

Share of New Cars by Emission Band (Source: SEAI 2014a Energy in Transport)

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

2016

YTD March

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

Shares of new private cars in each emissions label band

E (171-190)

B (121-140)

G (>225)

C (141-155)

A (<=120)

D (156-170)

F (191-225)