Ireland’s Environment – An Assessment 2016

46

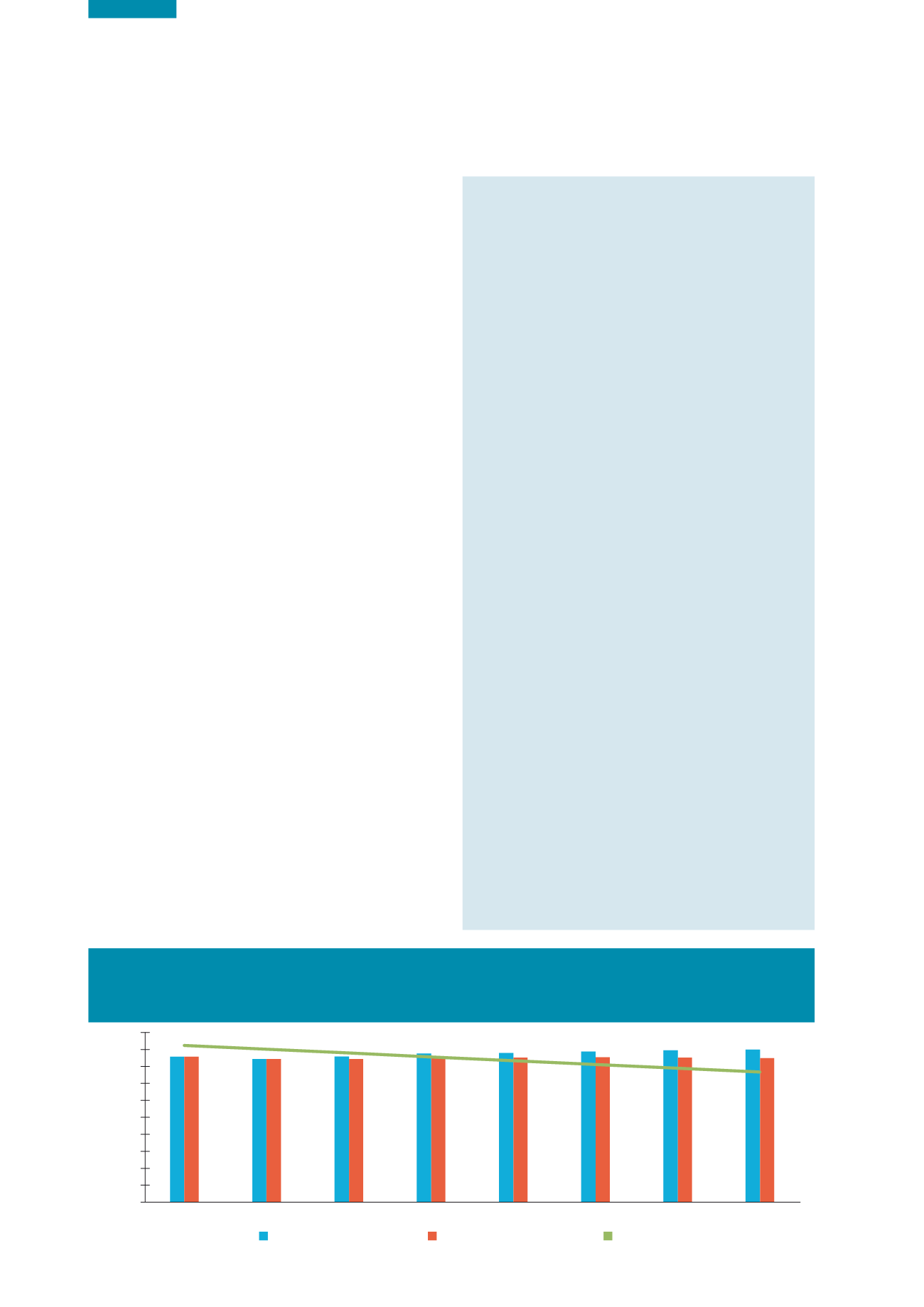

Emissions Projections

Projections suggest that Ireland will not meet its

emissions reduction targets.

The EU 2020 target is based on a combination of annual

targets from 2013 to 2020 to give an overall reduction by

2020. Official projections of GHG emissions to 2020 are

provided annually by the EPA based on two scenarios: (1)

with current policies, regulations and incentives (i.e. With

Measures, WM) and (2) with additional policies, regulations

and incentives (i.e. With Additional Measures, WAM).

These are depicted separately as blue and red bars in Figure

3.7. This shows that based on current policies, Ireland is

projected to exceed its annual limits in 2016 and, even with

additional polices, this limit would be exceeded in 2017.

For the period 2014‑2020, agriculture emissions are projected

to increase by 6–7%. Transport emissions are projected to

show strong growth over the period to 2020, with a 10–16%

increase on 2014 levels. Based on the two emissions scenarios

described above, total emissions are projected to be 6%

(scenario 1) or 11% (scenario 2) below 2005 levels in 2020

(i.e. WM and WAM). The target is a 20% reduction.

These projections are therefore a cause for significant concern

in the context of the anticipated requirements for further

reductions in GHG emissions in the period 2021‑2030. Failure

to meet the 2020 target would make future compliance

challenges more difficult and costly. In addition, the analysis

suggests that Ireland is not on track for, or projected to be

moving in the right direction, to meet its National Policy

Position, which aims to achieve a least 80% reductions in

carbon dioxide emissions by 2050 relative to 1990 levels and

achieving neutrality in the agriculture and land use sectors.

Further polices, regulations and incentives are therefore

urgently needed to meet existing targets and to move to

a pathway to achieve the 2050 transformation objective.

Increased strategic planning, investment and resources are

also needed to achieve this in the overall framework of EU

and global commitments.

Land Use, Land Use Change and

Forestry

Land management has a key role in the national, EU

and global response to climate change. The Kyoto

Protocol established a complex set of rules for reporting

and accounting for emissions and removals resulting

from land use and land use change. Ireland has

significant and healthy biosystems, including grassland,

hedgerows and forests, which sequester carbon

dioxide. Mineral soils and peat make up a large portion

of Ireland’s land areas and have high carbon content.

Under the Kyoto Protocol, Ireland currently accounts

for GHG emissions and removals associated with

forest land, cropland and grazing land. Peatlands and

wetlands are not yet included but constitute a major

area of carbon-rich land that needs to be protected.

Since 1990, Ireland’s forest area has expanded by

approximately 260,000 ha. As these forests grow

and mature, they will represent an important carbon

dioxide sink and long-term carbon store in biomass

and soil. The current national forestry policy addresses

these strategic advantages (DAFM, 2014).

In general, well-managed grasslands on mineral soils

tend to take up and store carbon in the soil. However,

changes from grassland to arable land, in particular,

can lead to significant carbon dioxide emissions as a

result of the disturbance of the soil and the loss of

vegetation above ground. Low-impact management

practices can mitigate such effects without

significantly reducing productivity.

The management of peatlands is a particular concern

with respect to potential for loss of carbon. Peat

extraction and change of use of drained peatland to

grassland or forestry leads to high rates of carbon loss.

In general, land management should aim to preserve

or enhance areas that have active carbon uptake

in soils and biomass, and reduce or eliminate areas

that are a source of carbon emissions. Such altered

practices also yield benefits for ecosystem services.

Figure 3.7

Greenhouse Gas Emission Projections Assuming Continuing with Existing Measures (blue bars)

and Implementation of Additional Measures (red bars) and Comparison with the Linear Reduction Pathway

Required Between 2013 and 2020 (Source: EPA, 2016b)

WAM Non-ETS Emissions

Annual Limits

WM Non-ETS Emissions

Mt CO

2

eq

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020