Ireland’s Environment – An Assessment 2016

132

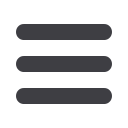

The most important health indicators of drinking

water are the microbiological parameters, in particular

Escherichia coli (E. coli)

bacteria. The presence of

E. coli

in drinking water indicates either that the disinfection

process at the water treatment plant is not operating

adequately or that faecal contamination has entered

the water distribution system after treatment. As shown

in Figure 8.4, the incidence of

E. coli

in public water

supplies in Ireland continues to decrease. However, the

microbiological quality of private water supplies remains

inferior to public supplies, with a significant number of

E. coli

detections in small private supplies and private

group water schemes. Furthermore, it is estimated that

up to 30% of the 170,000 unregulated private wells

in the country are contaminated with

E. coli

, which

presents a health risk for those consuming the water

(EPA, 2015c).

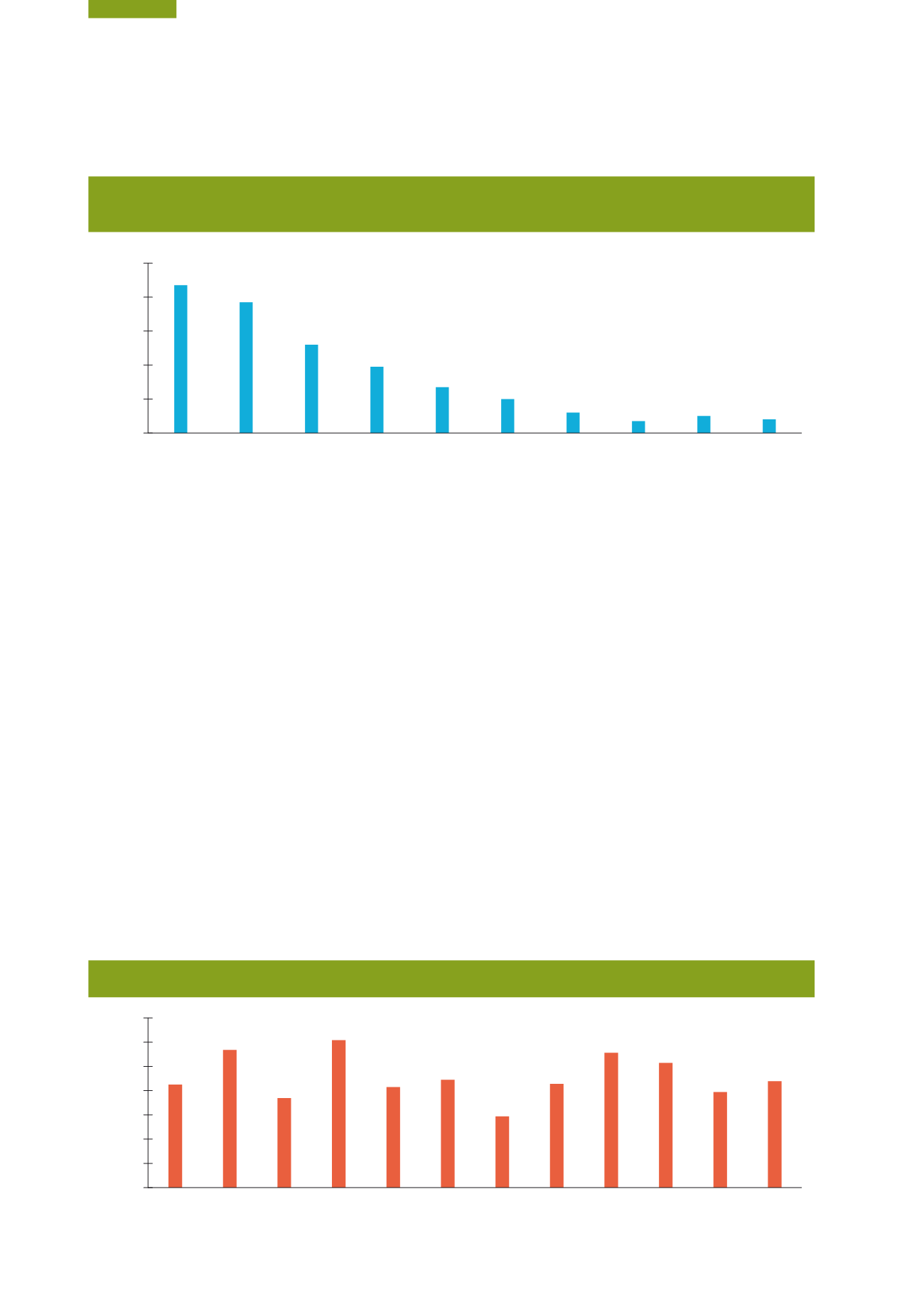

There have been cases of faecal-derived

Cryptosporidium

contamination of public water supplies in Ireland leading

to illness in the community, e.g. Galway City in 2007 and

Westport in 2015. These outbreaks highlight the risks to

health associated with the abstraction of drinking water

from poorly protected sources, and the need for modern

and well-managed water treatment systems. Figure 8.5

shows the number of cases of cryptosporidiosis reported

in Ireland between 2004 and 2015 (HPSC, 2015). There

were 439 cases of cryptosporidiosis in 2015, 10 of which

were definitively associated with drinking water supplies

(eight confirmed cases in a general outbreak in Westport

and two confirmed cases in a family outbreak linked to a

private well).

The winter storms in late 2015/early 2016 resulted in a

considerable increase in the number of consumers on Boil

Water Notices across the country as a result of a number

of supplies becoming contaminated with

Cryptosporidium

because of inadequate barriers at water treatment plants.

As guided by the EPA, Irish Water is adopting the Water

Safety Plan approach to managing drinking water supplies.

This involves a holistic process to identify, reduce and

manage risk, and thereby improve the resilience of water

supplies. This should result in a reduced risk to public

health of drinking water contamination.

Figure 8.5

Annual Number of Cryptosporidiosis Cases in Ireland, 2004‑2015 (Source: HPSC, 2015)

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

439

394

514

556

428

294

445

415

608

369

568

425

Number of cases

Figure 8.4

Number of Public Water Supplies in which

E. coli

was Detected in Compliance Monitoring,

2005‑2014 (Source: EPA, 2015c)

0

20

40

60

80

100

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007*

2006

2005

8

10

7

12

20

27

39

52

77

87

No. of PWS with E.coli detections

* EPA became supervisory authority for PWS with enforcement powers